Monsters are everywhere. We’ve populated cultures with them, sharp-toothed, taloned, primal and all-terrifying. Hunger given mouths. Fear given nature. We invent them now, still. Sew the scales and fur in skin not unlike ours and surrender ourselves when they catch us exhilarated and aghast. We collect monsters our entire lives. Some we keep; others set loose. We readily identify the monstrous in each other and deny others their humanity when we see fit. Distance is the only contingency to convince ourselves we’re anything else but monstrous.

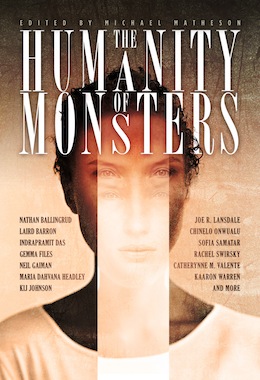

Michael Matheson sets out to examine not only the human in monstrous nature and monstrous in human nature along with their multitude intersections, but also interrogate and challenge the definitions of both as permutable societal constructs in The Humanity of Monsters. He describes the anthology’s focus as being about “the liminality of state”, which captures the ambiguous spirit exhibited in the collected stories. The monstrous reaches towards the human and vice versa in a beautiful half-transmutation.

With twenty-six works, it’s an ambitious vision to bring into being and it’s most successful in the unflinching, statement stories that work your heart over with a hammer, tapping into our disgust and gut fear on instinct. Gemma Files’ exquisite “The Emperor’s Old Bones” and Joe R. Lansdale’s “The Night They Missed the Horror Show” easily come to mind as the heaviest representations of reprehensible human amorality. Files and Lansdale remind us that humans are adaptable, can become desensitized to any atrocity if need be, and act according to a very arbitrary moral code. Yoon Ha Lee’s “Ghostweight” embodies all the points above as it follows Lisse on a revenge-fueled mission flying an exquisite spaceship class referred to as a kite (more of a death machine, really) in order to repay in kind the annihilation her world has suffered. This story is a staggering achievement in worldbuilding, space battles, and surprising twists. It’s a clear winner for the anthology.

A nice counterpoint to all this is presented by Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s “A Handful of Earth” where the reverse is true. You can transition into being a monster—the third bride of Dracula in this case—and retain the core of who you are, emphasized in the story through the protagonist’s adoption of the first two brides in the roles of younger sisters.

Horror of an existential nature grips the reader upon starting Peter Watts’ “The Things”—a retelling of John Carpenter’s The Thing, but from the alien’s perspective, which reveals its encounters with humans to be a soul-crushing experience for a distant star traveler seeking to take communion with new worlds. The monstrous in humans here is on a genetic level and elicits the same reaction of horror the original story’s characters upon encountering the thing in the movie. This story is then brilliantly paired with Indrapramit Das’ touching “Muo-ka’s Child”—a first contact story which follows a human travelling to a distant world and the result is optimistic, as Ziara allows herself to be taken into the care of the grotesque leviathan Muo-ka, who takes the role of a parent immediately. Whereas in “The Things” communication is tragically impossible, here it not only flourishes, but also bridges two very different species.

Mattheson has shown a knack for pairing stories together that examine different sides of the same coin. For instance, a chance romantic encounter is the catalyst for the events in Livia Llewellyn’s cerebral “And Love Shall Have No Dominion” and Nathan Ballingrud’s creepy “You Go Where It Takes You”. Both don’t end well and leave you with an unpleasant taste in your mouth, but for very different reasons. Llewellyn’s story destroys the woman who’s attracted the attention of a demonic force. This force, presented as male, annihilates its female host’s body and spirit as a desperate act of love, as it understands it—and perhaps the more frightening aspect here is how sincere, confused, and dejected it sounds. Ballingrud, on the other hand, brings single mother Toni into contact with a benign monster (for a lack of better word) and it is through a brief but intimate and meaningful interaction that she commences to act upon her current circumstances and change her life.

The matter-of-fact presentation of the strange and objectively terrifying works to a great effect and this technique of normalization and domestication also works well when Catherynne M. Valente uses it in “The Bread We Eat in Dreams”. Following the life that Gemegishkirihallat (or Agnes, to the residents in the small Maine town of Sauve-Majeure) makes for herself after her expulsion from hell, the story is the comprehension of human potential put to practice. Agnes not only has no ambition to terrorize the people in Sauve-Majeure, but she’s a contributing citizen, bringing delicious baked goods to the market and teaching young girls a lot about domestic duties and tending the land. It’s no surprise for anyone to guess what happens to a lone, prosperous woman in the early days of America.

As I’m running out of space, I’ll do my best to wrap up this review even though there’s so much to talk about. Highlights include Kij Johnson’s “Mantis Wives” and Berit Ellingsen’s short “Boyfriend and Shark” –both delightful morsels of fiction. Leah Bobet’s “Six” and Polenth Blake’s “Never the Same” both take a look at the social construct of what we see as bad seeds and monstrous behavior and challenge those notions.

Looking at the anthology in terms of overall experience, however, it becomes evident that Matheson has attempted to embrace too wide a scope and the threads dart in many different directions. While this conversation is multi-faceted, some restraint and focus would have benefited the overall reading experience. There are solid stories I enjoyed reading but did not see as contributing to the project’s stated goals, including Rachel Swirsky’s “If You Were a Dinosaur, My Love”. Also Moraines’ “The Horse Latitudes”, which works with language in a fine way and utilizes a dreamlike aesthetic to great effect. Wise’s “Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife” will forever remain a favorite of mine and a huge achievement in storytelling, but I had no luck in fitting it into the larger conversation.

Others were duds, plain and simple, which is almost inevitable in anthologies and when you’re faced with 26 stories chances are some will just not work. Taaffe’s “In Winter” felt more or less insubstantial. Headley’s “Give Her Honey When You Hear Her Scream” spun into tufts of strange imagery, which I rather liked on its own but didn’t work into a narrative so I left it halfway. Gaiman’s “How to Talk to Girls at Parties” was irritating (a complaint I’ve always had with his writing), even though I got everything he was doing and thought it smart work. Barron’s “Proboscis” and I didn’t click from page one. There are others, but I’d rather move onto the closing statements, since your mileage may vary.

As a whole, The Humanity of Monsters is gripping and Matheson has achieved his goal to question the divide between monstrous and non-monstrous: the book is an undulating, ever-permuting body caught in the same “liminality of state” that fuels its contents. The stories here are quick to rip off skin, scales and fur, and reveal that humans and monsters are more alike than we’d like to think. We bleed. We hurt. We’re all instruments to our desires.

The Humanity of Monsters is available from ChiZine.

Haralambi Markov is a Bulgarian critic, editor, and writer of things weird and fantastic. A Clarion 2014 graduate, he enjoys fairy tales, obscure folkloric monsters, and inventing death rituals (for his stories, not his neighbors…usually). He blogs at The Alternative Typewriter and tweets @HaralambiMarkov. His stories have appeared in The Weird Fiction Review, Electric Velocipede, Tor.com, Stories for Chip, The Apex Book of World SF and are slated to appear in Genius Loci, Uncanny and Upside Down: Inverted Tropes in Storytelling. He’s currently working on a novel.